Renaissance of Makers

Old status symbols fade and luxury takes on a new form. Making the most of our time — or rather, using time to make something tangible — is today's ultimate luxury.

Words:

Kate Swanson

Photography:

Leon Seibert

Decades of consumerism and globalization, coupled with greater levels of individual prosperity, have made traditional markers of luxury accessible to many. As a result, experiences like travel and fine dining are not the status symbols they once were. In their place, a new social currency is emerging, and it starts with time.

Why?

Time affords us the ability to make something tangible. And making the most of our time — or rather, using time to make something tangible — is the ultimate luxury.

Making equals luxury

A thought experiment: what do you think of when you hear the word luxury? Do you think of rare ingredients, molecular gastronomy, and a Michelin starred meal? Lounging on a yacht in the Caribbean, sipping on bubbly? Cruising down the Pacific Coast Highway in a vintage, limited edition convertible during the day, resting in a five-star hotel with views over Half-Moon Bay at night?

Not to put too fine a point on it, but these traditional concepts of luxury are outdated. Why? Because they have become too accessible. Perhaps not accessible every day, but our economy has shifted to allow these traditional markers of luxury to be democratized to the point that they are available to and can be experienced by a much larger segment of the population. Save your money and any experience can be yours. Anyone can make reservations at a great restaurant. Anyone can charter a boat for the day. Anyone rent that vintage convertible for an idyllic California road trip.

But if these experiences do not symbolize luxury, then what does?

Modern day luxury is not simply an experience you buy.

Modern day luxury means looking at, ironically, the one thing we all have in equal measure: time. How much available time one has, what one chooses to do with that time, and what they are capable of achieving in that time: this forms the basis for a new status symbol (of sorts). It is not necessarily time in the context of “I have all the free time in the world”, but time in the sense that, “While I may have limited time, I am capable of using it efficiently, using it to maximize my potential, and can show a tangible outcome for my efforts.” It’s about having discipline. It’s about perseverance. It’s about evolving your own personal capacity to reach a place where you can master an art, and prove your ability to make something real.

Applying one’s (limited) free time to the pursuit of a new skill that results in the creation of something tangible — this brings us closer to achieving the new luxury, a luxury where making it, and making it well, is the marker of success.

Why do we see maker culture

The rise of maker culture can be attributed to many factors, but we’ll focus on the three factors that we see most prominently.

First, a rejection of the norms set by generations immediately before us. Those who flocked to “instant” solutions and saw the maker process as slow and tedious — one that could be eliminated or reduced by new technologies and new methods — believed that eliminating “the need to make” was a marker of luxury.

While there are advantages to instantaneous results in certain contexts, instantaneous is also likely to mean mass produced, processed, or altered, and is unlikely to mean quality, natural, or healthy, making it highly undesirable in many circumstances (as we are coming to terms with more and more every day). Increased transparency into harmful processes and ingredients that go into what we consume — especially the “instant” version — paired with education about the way food affects our well-being have shifted our attitudes. As we learn to reject the “instant” version, we force ourselves to go back to the basics, and in doing so, re-learn how to prepare a version from scratch.

In other words: make it.

Second, it’s a response to the fact that, for many of us, we don’t actually make things in our daily lives. Deals closed, code written, cases won, strategies implemented — we work in intangibles all day long, none of which amounts to something we can hold up and say, “I made this.”

Third, looking specifically at the food context, it’s the proportional response to the now widespread, on-demand availability of pre-made meals. While UberEats, Grubhub, and the like are amazing (and we can’t imagine life without them), we don’t associate them with special occasions. We associate them with work and a lack of free time. Late nights at the office spent on due diligence, drafting deals, waiting to complete another turn of a document — this inevitably goes hand in hand with some kind of meal, delivered to the lobby of the office tower where you toil. To that end, while the convenience of on-demand delivery may have started as a luxurious access point to whatever food you desired, it has turned the act of eating take-out to yet another way you can be kept at your desk. In contrast, the act of making your own food, feels like a luxurious departure from the office; a marker of freedom and life outside.

And so, in defiance of a world where we are expected to work more and more, there is something liberating and sacred about the act of not ordering in, and instead, making food for yourself.

As these three cultural waves collide, we are thrust into a search for quality and authenticity, finding out that we relish the opportunity to put our free time towards creating something tangible. In part, this means returning to processes likened by our grandparents’ generation — a time when making it was the only way to get it — but it also means looking for modern tools to take what we’re making to the next level.

Where we see maker culture

The new luxury behind makers takes many forms. Do you hand-make guitars in your spare time? Create custom joiners to build bespoke, Japanese-inspired shelving? The luxurious outputs of maker culture are everywhere. But, perhaps, nowhere is it more apparent than in the kitchen.

Recalling two recent conversations with acquaintances in New York:

- The first, an investment banker: “At the end of the week, exhausted as I might be, there is something so satisfying about cooking. Even if all I do is sear a steak, it makes my entire week feel better. I am in control. I can be creative. Just being able to make that one thing — it makes me feel real again.”

- The second, a partner a venture capital fund: “In this job, I am always working, always juggling. Even though I have little free time, I really like to keep busy — I don’t want to come home and just stop. I’ve started baking. I like to perfect things. Next on my list is croissants. It’s going to be challenging, but I think, five or six batches, I should be able to perfect it.”

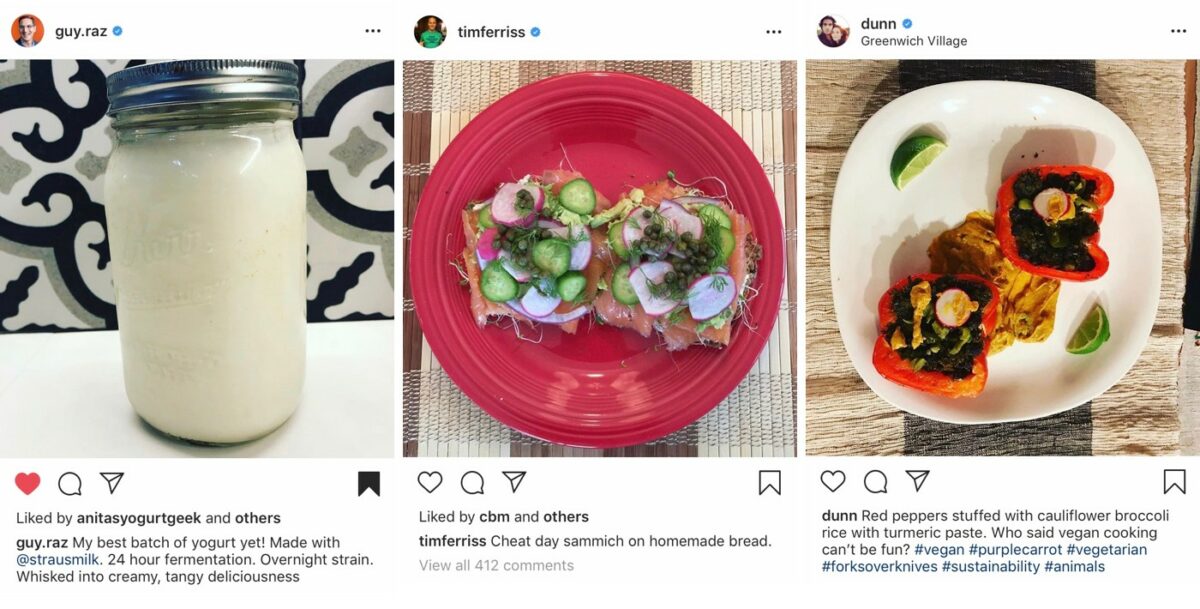

And, recalling a few posts that caught our eye on Instagram courtesy of Guy Raz, Tim Ferris, and Andy Dunn – each with their own unique approach to “making”.

How do you become a maker?

Maker culture is founded in the idea that before you make, you must understand. And maker culture in the kitchen is no exception. As such, with the rise of makers, we are seeing a surge of interest in understanding our food. From understanding where our food comes from, how that impacts flavors, to understating how to prepare, combine, present, and serve — one must invest time understanding the details, effort mastering the technique, if they want to truly perfect the art of making.

The rise of maker culture has also spawned a shift in the kitchen — meaning a shift in who we see cooking and who we see perfecting the food they prepare. Maker culture does not mean lawyers are leaving private practice to start over at the Culinary Institute of America. Instead, it means that one can continue their professional pursuits while simultaneously levelling up in order to master the art and science behind making.

More Stories

-

17.11.2025 | News

Black Friday Sale - 45% off everything *including Stackware*

17.11.2025 | News

Black Friday Sale - 45% off everything *including Stackware*

Our biggest (and only) sale of the year is here. Over $460++ off cookware. 45% off everything.*

-

05.11.2023 | News

Celebrating with Rolls-Royce

05.11.2023 | News

Celebrating with Rolls-Royce

Bringing design, innovation, sustainability, performance, luxury, and craftsmanship together.

-

01.11.2023 | News

Utility Patent Granted

01.11.2023 | News

Utility Patent Granted

The ENSEMBL: Stackware Removable Handle has received a utility patent.

Free shipping on all North American orders.